A couple of weeks ago, a Ukrainian journalist, Nastya Melnychenko, published a post on her Facebook page hashtagged #яНеБоюсьСказати (#iamnotafraidtosayit), where she openly told stories of sexual abuse she experienced in her life.

She also invited other women and men to join in and share theirs. It’s time, she said, to stop hushing up the problem, it’s time for victims of sexual abuse and gender violence to stop feeling shame and blame themselves, it’s time to speak up because this problem is not a problem of any individual victim, it’s a problem of entire society.

And that was how the flash mob that is currently making waves and rapidly spreading from country to country started. Thousands of people, mostly women, shared their stories for the first time in their lives, stories of abuse and harassment they had lived with in silence for ten, twenty, or more years. Tens of thousand of other people commented expressing support, disbelief, or hatred.

Only time will show whether this outbreak of pain will lead to a large scale surgery that will only be able to cure our society from a disease that has been torturing us for millennia uglifying and crippling everybody – victims, abusers, and indifferent witnesses. But for right now it feels as if a huge abscess has finally bursted and the pus is starting coming out. It’s painful, it’s ugly, it’s smelly. But we need this. Unless we go through the stage of cleaning the pus, we won’t be able to overcome the disease and move forward as a stronger and healthier society. Meanwhile it’s important for everybody (everybody!) to stay patient, tolerant, honest, and involved. Being involved is important because this problem is everybody’s problem that affects the quality of life of every person, whether man or woman, every day. If it hasn’t happened to you, it has to at least one person you know and love, and because of this mutilating experience, this person is now not what she or he could have otherwise been – they are less confident, less trustful, less open.

I’m supporting this movement full heartedly and will share my story too. Even though it’s tough.

I was 6 years old. Back then in Russia we started school when we turned 7; before that we had to attend daycare. So I was in daycare that day. It was later in the afternoon, almost all kids had already been picked up, only three of us left – two boys and me. We were outside in the playground. Our teachers were sitting on a bench and chatting. These two boys were not whom I usually played with so I was pretty much on my own plying with myself in one of the corners of the playground. At some point, the two boys approached me, grabbed me, and pulled me into a pavilion in the center of the playground. One boy was much larger than me. He grabbed my both arms and hold them tightly behind my back. The other boy started kissing me on cheeks. It was very disgusting but I didn’t dare to call for any help because somehow I felt that the situation was my fault – I failed to be picked up earlier and now had to face the consequences of being the only girl with two boys on the playground. Besides, I knew that teachers would probably blame me anyway, not boys. We had situations like that before and teachers routinely blamed girls for letting boys “play” with them in such ways.

Anyway, the kissing lasted for what seemed like forever until my grandma finally came to pick me up. She wanted to give me a hug and a kiss as usual, but I recoiled from her in horror thinking I was contaminated now and fearing she would catch the taint I felt on my cheeks. I might even hurt her by my rudeness, but I couldn’t explain anything to her without making my shame public. When we finally came home I rushed to the bathroom and started washing my face. I washed and washed, with soap and shampoo and whatever else I could find. Then I started brushing my cheeks with toothbrush, painfully scratching the skin. But the feeling of taint on my cheeks and the sense of shame did not go anywhere. I never cried, I never told a word about the incident to anybody. And I haven’t forgotten it either even though it happened decades ago.

Later in my life I’ve experienced regular harassment on streets and occasional touching of private parts in crowded places. But that first incident in daycare, no matter how innocent it may look, still feels the most humiliating to me. I think it’s because it was my first experience of gender abuse when I was humiliated as a girl and when my body was used by force by members of another gender for their own purposes. The incident pushed me to face the reality of women’s life which seemed to inevitably be accompanied by injustice, humiliation, fear, and shame.

I wasn’t the only one who learned her lesson that day. The two boys also did. By committing an act of violence against a girl and not getting punished for it, they learned a concept of impunity – they can get away with violent actions as long as they direct them against women. What is also reveling about this incident is that the society, in my case our teachers who definitely saw what was going on, didn’t interfere to stop the violent behavior, less though to restore justice or educate. The teachers, both females, had probably seen a lot of scenes like that and learned to trivialize the drama behind them; they might also experience similar episodes when they were kids and most likely came to conclusion that for women to be sexually abused by men was a natural part of life – horrible yes, but unavoidable. Apparently it was the same conclusion I came to that day that “prepared” me for later episodes of harassment and “helped” me live through them, even though every time I got mad and wanted to kill the abusers.

Reading stories of sexual abuse written by other women (and men!), I’ve found a lot of similarities. One of them is that many women experienced their first gender abuse at a young age; at that they didn’t know what to do, blamed themselves and didn’t say anything to anyone. Shock, shame, and fear were common words women used to describe their feelings.

Second, in the majority of these incidents society (meaning basically adults around) didn’t get involved leaving the problem to individual victims to deal with – to swallow, forget, let it go, etc. As it was the case with my daycare teachers, adults or authorities in other women’s stories didn’t try to establish justice, increase awareness of the problem, punish abusers, and/or help victims thus ensuring the continuation of a millennia old vicious cycle when abuse creates abusers who in turn create more abuse. I will talk more about the reasons behind such behavior in my following post on the same topic.

Thirdly, all stories I came across happened decades ago. Nobody talked about a recent incident, even less likely about current abusive relationship. It’s still too much. And too dangerous.

A final observation I’ll share is that many women started their stories by describing what they were doing when they were attacked and why – “I had to take the late bus because our boss kept us in a meeting for too long”, “I had to stop by grocery to buy food”, “I was sick and stayed in bed longer than usual” – as if trying to prevent accusations in provoking the situation themselves. Many women also described their clothes to explain that they didn’t look sexy. In the beginning, it seemed very natural for me to read. But then I realized that it was not natural at all. It is actually absurd that women, victims of abuse and rape, have to prove that they didn’t want to be raped, that it was not their intention, and that they didn’t plan it by any means.

Ok, enough. I feel it’s becoming too depressing so let’s switch gears and go to the positive side of the flash mob.

What’s good about #IAmNotAfraidToSayIt and why I support it.

- The flash mob addresses a typical for all cultures of violence practice of blaming the victim of the assault. For all our recorded history, it was women who were charged with their own rape and punished by shame, ostracism, or even killing. This culture has not gone anywhere even though it’s 21st century. For a modern woman to openly tell about being raped feels like another rape and customarily comes with shame, humiliation, and fear. The flash mob attempts to break this culture. When thousands of voices come together sharing their stories, sexual assault stops looking as a problem of an individual woman, rather as a systematic problem of the entire society. Even though it will take thousands of flash mobs like that to start changing the culture, every one is important.

- The flash mob offers an alternative solution to a problem of low sexual abuse reporting rate, a problem that is tightly connected to the overall culture of blaming victims. Whether we like it or not, but this flash mob is one of a very few ways currently available for us to estimate the scope of the problem. No official source has this information because women simply do not report.

- The flash mob attempts to destroy impunity of abusers. From early age boys learn that they will get away with sexually aggressive behavior towards girls because girls simply won’t tell anybody anyway to avoid further shame, as it happened with the boys and me in daycare. But flash mobs like this can reverse this trend and initiate yet another very needed for the health of our society cultural change. Perpetrators will learn that their deeds will be if not punished in court but at least damned in public. Note, there is a legitimate concern that some men may be accused falsely. It is an important question and I’m planning to address it in one of my future posts.

- The flash mob increases an awareness of a problem we have routinely ignored and passed by in silence for long-long time. For many people, particularly men, the flash mob proved to be eye-opening. In their comments, they said they knew that the problem existed, but perceived it as a distanced one, a problem that had nothing to do with women around them, women they knew and loved. Reading story after story, they were horrified by the scale of sexual abuse and even recognized themselves in indifferent witnesses who tolerate and accept as a norm sexual harassment towards women on streets and in offices.

There is one more important benefit I see. Many women who were sexually abused as girls or young women and never told anybody about it, now can finally seek some justice and support, if not official but at least as a human being. Women who have lived with their memories for decades can finally speak up and hopefully let these horrible physiological burden go.

Now, what is very important NOT TO DO when we tell stories of sexual harassment is to not generalize, to not express your anger against ALL men or ALL women. Please! It’s crucial for everybody including you to not equate a minority of sexually aggressive men and women with all men and women. Research has showed time after time that the majority of all gender violence incidents are committed by a limited group of people. By no means gender violence can be portrayed by picturing all men as sexual abusers and all women as their victims. No. Gender violence looks more like a sexually aggressive minority (mostly men, but also women) commits a large portion of violence making the majority suffer. The aggressive minority rules here as everywhere else where the violence is above the law.

And this is what this flash mob is eventually about, as to me – it’s an attempt to change the perception of gender abuse and show that it is not about men abusing women (or women abusing men) but about sexually aggressive minority abusing the rest of us, it’s an attempt to start changing the culture of violence that still determines the relationship between genders.

In my second post on the same topic I want to explore the reaction to the flash mob from and the results.

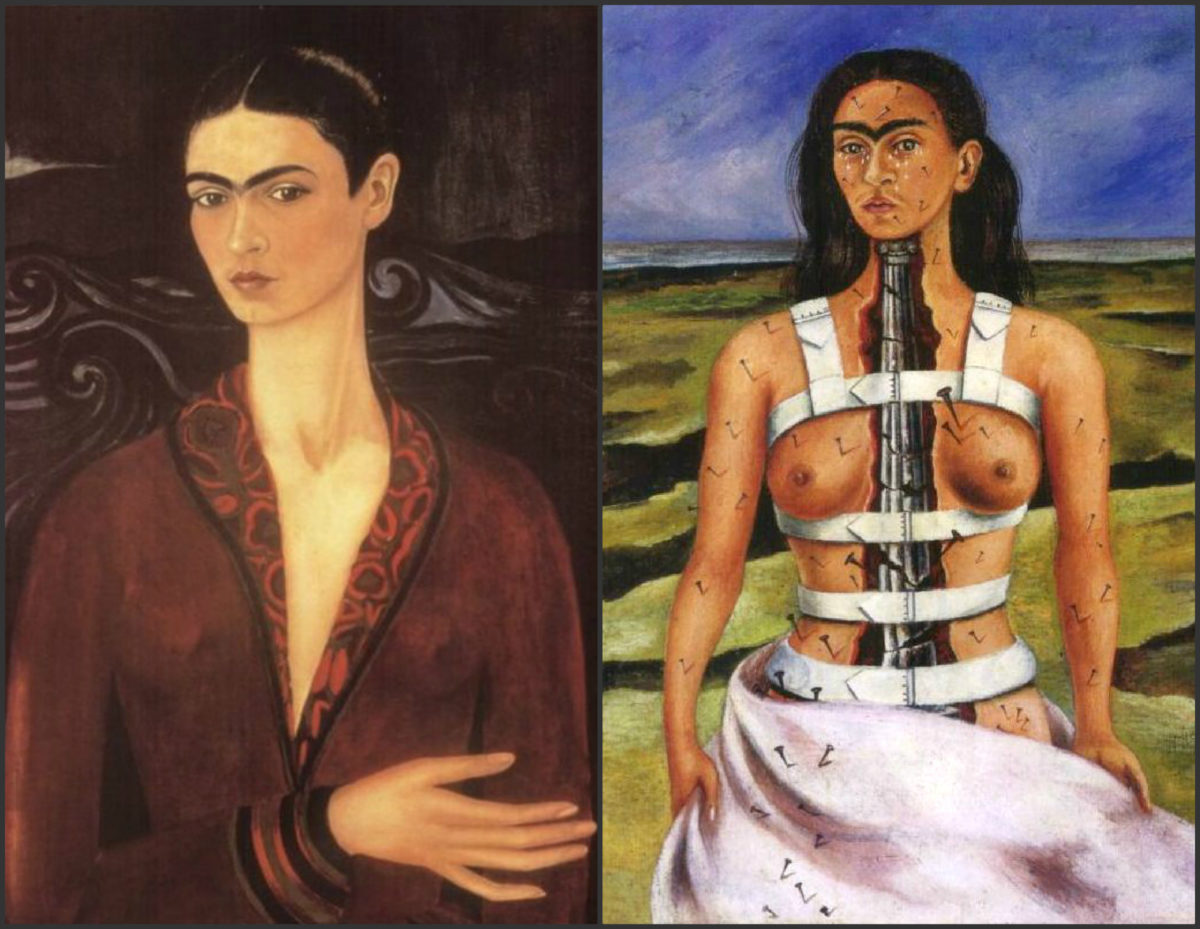

Illustration. For the cover photo I chose two paintings by Frida Kahlo – “Self-portrait in a Velvet Dress” and “The Broken Column”. As you most likely know, when Frida was 18, she suffered a bus accident that ruined her body and caused her many sufferings in life. I see a parallel here with women who suffered from sexual abuse, whose bodies were violated and whose personalities were humiliated by the experience. From outside they may look beautiful, same way as Frida portrayed herself on the left painting after the accident, but from inside they feel crippled, mutilated, pierced with pain of memories and injustice.

1 thought on “#IAmNotAfraidToSayIt”